How belief bends reality

When I was the GM for a popsicle company, it was my job to get our pop slingers out the door on Saturday mornings. We worked a lot of farmers markets, so we had to have dozens of pushcarts packed with pops and dry ice and loaded into trucks by 6 or 7 am.

These mornings were hectic, to say the least.

Imagine a bunch of twenty-somethings running in and out of walk-in freezers, jostling for space in a crowded warehouse. Once packed you had to run up the street and find your assigned truck before backing it into the tiny loading dock. The whole thing had the frenetic energy of a kitchen in a busy restaurant.

I would spend an inordinate portion of my Fridays writing out a detailed plan for the next day on a massive whiteboard, and curious employees would always stop by to take a peek.

“How’s it looking?”, someone would ask with trepidation.

My answer was always some sort of sarcastic, self-deprecating response about how hungover and late everyone would probably be or how chaotic it was going to get.

And it was always chaotic (albeit a fun sort of chaos, most of the time).

Then one day our management team attended a workshop run by Ari Weinzweig, the co-founder of Zingerman’s Delicatessen, in Ann Arbor, Michigan. It was there that Ari introduced us to something called the “the belief action cycle”.

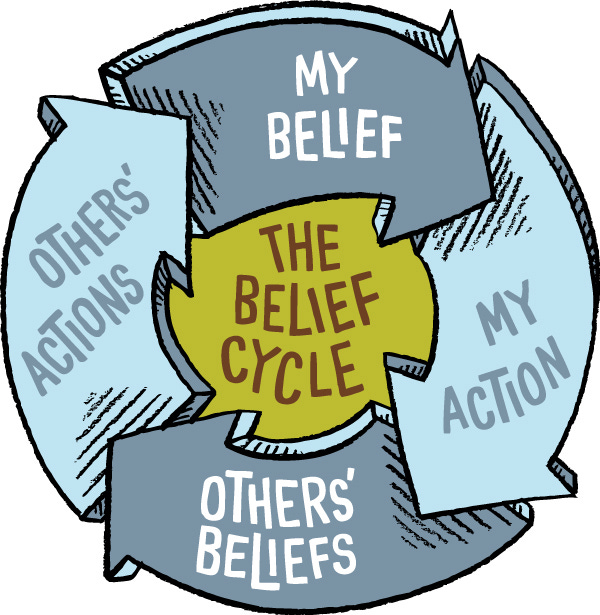

The belief action cycle works like this: Whenever you hold a belief, it will inform some associated action you take. This action is observed by others who then generate their own beliefs, which informs their actions. Their action then reinforces your original belief and the cycle continues.

Here is the image Ari used when explaining it:

I didn’t believe that young people could make it to work by 6 am on a Saturday, so I took actions like making snide comments or artificially moving up their start time on the schedule to build in a buffer. Employees witnessed these actions and formulated their own beliefs: “My boss doesn’t think I can do this. He seems smart, so that’s probably true.” That belief informed their actions—staying out too late the night before or rolling in 30 minutes late. Which of course reinforced my original belief that they couldn’t do the job.

We managed to break this vicious cycle when I started changing my tune at the whiteboard on Fridays. Instead of lamenting about how hard the day was going to be, I kept things positive. “It’s going to suck” turned into, “Y’all are going to crush it”.

(Yes, sometimes you have to force the belief before you totally believe it.)

Did this solve all of our problems? Of course not, but it helped immensely.

I recently read Walter Isaacson’s excellent biography of Steve Jobs. By the time I finished it I was convinced Jobs was a deeply flawed man who no one should ever fully emulate, but I was also in awe of his ability to motivate others through the power of belief.

My favorite story in the book is about the launch of the original Macintosh. One week before it was due to ship, Apple engineers realized they weren’t going to make the deadline. A software manager, chosen to relay the news to Jobs via a conference call, carefully explained the situation and asked for two more weeks.

Job remained silent for a moment while the the engineering team held their breath on the other end of the phone. Here is Isaacson describing what happened next:

He told them they were great. So great, in fact, that he knew they could get this done. “There’s no way we’re slipping!” he declared. “You guys have been working on on this stuff for months now, another couple weeks isn’t going to make that much of a difference. You may as well get it done. I’m going to ship the code a week from Monday with your names on it.”

They now knew Jobs believed they could complete the Macintosh on time, so they did it. The book is full of examples of Jobs using his “reality distortion field” as employees called it, to push people to do what they had previously thought impossible.

Actions (and therefore results) are the product of beliefs.

What are yours?